Investment Pathologies

"Disinvestment of capital, namely assignment of a much smaller part of total production to goods which are instrumental and non-consumable"

(Point "a" of the Revolutionary Immediate Program within Western Capitalism, Forli' Congress of the International Communist Party, december 28th 1952).

Today

Culture is progressing. Small businessmen in front of a video banking terminal enter into lively discussions about fundamentals and mergers. It's not true that radio and television broadcast only stupid songs, cretinous shows and old movies swamped by advertising. Economics too has its room, and careful housewives even pay attention to programmes presented by serious-looking professors. Magazines that aim at making you millionaires, capitalists and economically engaged are spawning. Investment is an earnest thing. The internet invites you to click on the "finance" button. Government bonds aren't profitable, but you'd better leave futures to the specialists. So, trust the experts and invest in mutual funds. And, if you are a thrill-seeker, try "day trading" on the internet, where commission is quite cheap. By now, there's no bank that's not publicizing its "on line" service. An american lad was able to waste a whole inheritance, about half a million dollars, in a day's span; an office clerk slew his family and commenced killing people at his firm because he had lost his "touch" at investing. But these are isolated cases involving varieties of "crackpots". Therefore, the slogan is no more "save", it is "invest". In a period when industrial investment is slack, virtual investment is booming. Capital cannot remain idle, period.

Now that capitalist economy has left behind the investing euphoria of post-war re-construction and the global inflation crisis of the 70s-80s, it seems to have stabilized around low rates of growth in production with low inflation. The great corporation, that is, the government, industry and trade-unions altogether, is no longer speaking of productive investments, as in the cherished times of the boom. The flat conjuncture affects the theories animating states, banks, fund, managers, etc. The economists have thereby gone over from an unrestrained optimism as to an unlimited growth in the post-war period to today's grave concern about capital's physiological limits of growth. Most of them, anyway, calm down while beholding the curious phenomenon of a stock exchange retaining its "sparkle" in spite of the all "fundamentals" which should be damping its ardour. But, there are some who warn against the excesses of unbridled capitalism. Three nobel-prize winners, the US Minister of the Treasury and his collegue at the Federal Reserve have striven to explain that sooner or later the bubble would burst, and have attempted to deflate it in a timely manner by threatening high interest rates. Every expert seems quiet, but fear creeps in and they try not to spread it; no one indulges any longer in catastrophism, as they did in the years around the oil crisis; no one risks forecasts; now, navigation is "by sight", while hoping to make it. This is to say that political economy, rather than an exact science, as its scholars claim it to be, follows where the financial wind blows . It's well-known that in the financial sector astrologers are sought for advise, maybe the Madonna too is called for help with votive candles.

That's nothing new. However, it's clear that even among the most restive economists, those who will never acknowledge the inner limits of capitalism, that today's situation is seen as irreversible. No one believes any longer that such a low growth of newly produced annual value is a temporary thing, and that in the West post-war capitalism may come back, with its double figure rates of growth. Moreover, the conjuncturally more dynamic Orient will have to accept this decreasing trend over time.

That's why investment must be rapidly directed towards the stock exchanges, where sometimes the double figures pop up again. The breath-taking swings and the general trend upwards seem to issue out of a curious autonomy of the financial sector from the main economical data, that is, good old profit, its steadiness anchored in industrial development. Instead, it's the very lack of a solid industrial alternative that explain the more or less open speculation and its eye-catching effects.

The fact is that, taken alone mutual funds have invested 25,000 billion dollars. And this mountain of money, even if it belongs to scores of scattered capital owners, as a whole, however, is able to act in the market in a co-ordinated fashion. In this sense, the general structure of world investment is altered from the past, not because such funds didn't exist also many years ago, but because quantity has turned into quality. Never in history, even if the due proportions would be calculated, has such a great amount of capitals come into the market, all claiming a sure "profit". Retirement funds must pay millions for people's pensions. Insurance funds, in turn, must pay for illness, accidents, unexpected expenses, etc. And the open investment funds must bring into their portfolios such titles as to give very attractive results, otherwise their investors say good-bye. So, their administrators buy stocks that are already high, causing them to go up further.

The system has become strongly self-referential, and it's well-known that in nature, this is a source of troubles. No one can predict what is going to happen if this staggering balance should blow up. So, governments themselves, when attempting to keep it from blowing up, can't help adding to its explosive potential. In such a situation, it's impossible not to comply with all the frenzies of investment of capital, which has become anonymous, through its collective administration becoming more and more gigantic. And so, every illusion is falling, like putting the system in equilibrium, gaining ecological control of industry, recovering from environmental disasters, prevention regarding the obvious diseases of the planet. Investment, instead of becoming a controlled phenomenon helping to humanize capitalism, as its apologists claim, becomes a wild turmoil liquidating the worst mass murder as an accident on the way, and environmental destruction as a necessity.

In the early 70s, it was presented, on request of the Club of Rome, a famous work of prediction, entitled The Limits of Development. With data of dynamic economic models processed by a computer, it was proved to be close the limit beyond which the world's economic relations would run down irreversibly to the catastrophe (the point-of-no-return being situated at around 1975). Its authors warned about mechanically interpreting this model, but pointed out that, even though its parameters could be realistically modified, and while surely the time span would change, its catastrophic outcome would not. Twenty years later, the same model was up-dated, upgraded and processed again. Twenty-year old data for prediction were replaced with real data which characterized the world economy in the meanwhile, and the projections were updated to the subsequent twenty years. The simulation didn't change the previous results, confirming that the limits had already been surpassed. According to the new model, mankind might still save itself, but only with a gigantic effort of all the states of the world united in order to determine the quality of investments and lower the threshold of risk. No one, however, was able to say how to carry out such a task.

In the same period, many economists or scholars of economic issues based on the dynamics of the system, were seeking to prove in countless publications that mankind was at a bifurcation point, beyond which there was either a correction in the direction of the world economy or catastrophe. Some, taking the laws of physics as a model, demonstrated the entropy of the capitalist system, that is, its loss of energy, its running down into chaotic situations), whereby stability could be reached only by means of a reasoned restriction of the economical parameters (such as investment, growth, demography) and of their harmonization with the environment. Others, on the request of the U.N.O. proved with different and more sophisticated models that mankind would set out towards a further, unsustainable gap between those with more and more reserves and those with less and less reserves. There were some, moreover, who, bordering on mysticism, held it to be necessary to deconstruct capitalism, and to return to more natural production techniques, with a much lower use of energy and of highly polluting raw materials, renouncing destructive and exhausted technologies and consumerism.

This return, à la Rousseau, to a "state of nature", blurred in its outlines but substantially capitalist, is an American speciality, and many even try to practice it. These people badly miss a nature which no longer exists, and are oblivious to one simple thing: today's human condition is a result of the "natural" evolution of the species. Thus, the question isn't that of returning to a previous stage, but that of ending the sequence of the social forms acting unconsciously with a plan based on the species itself, and of using the potential the species has achieved for a conscious harmonization of man and nature.

Despite a spawning of more or less alarmist if not catastrophist schools, either scientific or simply mystical, but all reformist in the final analysis, the only realistic prospect of the states' economy remains growth and investment, with an eye to the financial markets, to which consumption and exports are linked, under the control of a traditional monetary policy. The supreme deity in the context of this quite trivial policy remains the GDP anyway.

This parameter is divinized for the simple reason that it is the only one having some foundation in the whole bourgeois economic construct. It is, in fact, the new value produced annually by a given society, or, to put it another way, the sum of wages and surplus-value.

As a quantity symbol, the GDP isn't a "well-being" index, as the official statistics try to pass it off : in fact, it can increase – and often does – also in the case of serious malfunctioning of the whole society as a result of its disorder and dissipation. For instance, it's clear that, in case of an irrational trend of transporting more goods by road than by rail or waterway, there would be roads obstructed and in tatters, massive consumption of fuel and tires, vehicles worn out and generalized pollution provoking various diseases. As a result, there would be bigger profits for truck, fuel and tire vendors, for those building and maintaining roads, for pharmaceutical firms, etc. On the other hand, there would be also an increasing of jobs, then of the national income, with a wanton plethora of truck drivers, specialists of pollution and stress pathologies, administrators of related industries, etc: the more the confusion, the greater the increase of men and means to face it.

Usually, when the contradictions of the system are being criticized (even if only en passant, for instance, by an academician publicizing his hoped-for best-seller on the coming catastrophe), the economists close ranks and reply that since 1900 the average lifetime has increased twofold, consumptions have increased sixfold, services threefold, fifty percent more food is consumed than before, indeed, that today's welfare is incomparable with that of one hundred years earlier.

All this – which is the usual average of the chicken: one person gets to eat two of them and someone else doesn't get any – is true, but it is also true that, if consumpion is six times as much, one can eat roughly as much as a century ago, apart from what industrial food is made up with. That's to say, this doesn't prove at all that men's needs are really fulfilled, unlike those of Capital, which are quite another thing.

Capital has no regard for mankind's quality of life. Rather, quality is equal to quantity, whatever is the need generated by the type of consumer goods, provided that this consumption enables the whirling cycle of production and surplus-value to continue expanding.

It follows that the economists, all-in-all, just give councils of good will, as sterile as their calculations. They may continually issue petitions of reform, proving its necessity with impressive or unusual models, which relate more or less strictly to science; those who see the catastophe coming in a more or less brief time may call out "Danger!"; governments may order detailed studies, inevitably resulting in the obvious conclusion that there is a contradiction between unlimited, exponential growth and a finite world; in sum, they may prove, altogether, that staying this course is impossible; all of them together, however, can say nothing when summing up and suggesting a viable practice to counter all the troubles. They all appeal to governments' good will, as if governments were able to control Capital and it wasn't Capital that controls governments' action. The one mechanism Capital knows is the production of surplus-value by exploiting the labour-force, its realization through the market, its investment back in activities producing further surplus-value, and so on, in whatever way this course is to be accomplished.

And when either a capitalist or a shareholder aims to get a certain profit rate, that means his anticipated capital must become bigger and bigger, cycle after cycle. That's why growth is a damnation capitalism can't escape. That's why the reformists, whether catastrophists or those slightly more optimistic, must spout nonsense. The fact is that balance doesn't exist, and disinvesting is a stupidity, when uttered by reformists who definitely do not want, God forbid!, the death of capitalism. But, disinvestment, for capitalism, is its own death.

To all of them comes the nobel-worthy economists' reply, those teaching in the universities and being consulted by the government, those well aware that their fees depend strongly on advising some simple and viable things which a parliament can pass: that is, wishes of good will, that is, nothing. They hold that growth is compatible with the resources and finitude of the earth, provided that the market is given free reign, with a few correctives by law. You know, even the most doctrinaire of the "free-traders" claims that the state must enforce the free market against its spontaneous trend towards monopoly. In reality, the dispute between state-interventists and free-traders doesn't exist, considering that both of them want the state to intervene: they only suggest a different degree of intervention. However, they are all silenced by the daily routine of the economy, where the US federal reserve changing the interest rates by a point can affect the trend of the world economy. But it's the latter that imposes the decision upon the man who seems to make it.

It's in such a context, as complicated as it is insensible to men's solicitations, that investment, whether industrial or financial, is being still spoken of, as if the direction capital takes would depend on a capitalist's decision. Once upon a time there was a capitalist who had free reign on his profit and in planning by himself the fortunes of his factory. Now the fairy tale is over. The most sophisticated computer models show, as does reality, that every economy based on value loses equilibrium while growing by quantity, but, above all, loses sensibility towards regulating interventions (is entropic, they say); thereby, free-trade ideology takes over for material reasons: they can't do anything else. Today's political economy privileges two items: capital and consumption, and doesn't mind of what precedes them (men and available resources), what is in the middle (production) and what comes after (men again and modified environment). Since the early separation of society into classes, men have never been treated very tenderly by other men, they has been continually enslaved and slaughtered in countless ways: but never as much as today has man been reduced to a simple powerless appendage of a force overwhelming him; every social attention towards the much vaunted "person" is viewed by political economy as thwarting the sublime heights to which capital must soar. People are mistaken if they think, while reading an economic article, that the "fundamentals" spoken of mean investment, production, organization, labour, energy, intelligence, social welfare (another idol that has tumbled down), etc. No, the fundamentals are profit, productivity (that is, so much profit for so few workers), a solid capitalization in the Stock Exchange, the rating (solvency index). Thus, a firm that is worth nothing according to the old rules, that doesn't produce a damn thing, and that is continually in the red (financially, of course), like certain of today's "technological" firms, can be immensely successful and attract capitals from all over the world. Here is modern investment.

Naturally, capitalism itself couldn't survive if there weren't somewhere a scientifically organized production making goods for sale and realizing surplus-value in order to feed the hysteric hunger of financial gain. Paradoxically, holders of capital big and small despise this industrial world upon which the big casino of the finance rests. They invest in a more and more indirect way, and pay as much indirectly managers and technicians making this sector operate, although they are hard pressed by an enlarging gap between a need for profit in the shortest time and the needs of production, which abhors improvisation and which makes mid- and long-term plans.

Politicians and economists are prostrated by this fait accompli, so they ideologically surrender trying to govern a system that has peaked in its maximum complexity and from time to time churn out theories re-cycling the old tunes about laissez faire and the market's invisible hand. Such being the premises, it's logical that the accepted social pattern indicates "well being" as something which can be measured with the only possible parameter: the quantity datum of accumulated capital. And if this is the one datum that can be taken into account, it's equally logical that capital's growth is meant to be unlimited, which, obviously, in a time projection, would require, at least, that the earth could be multiplied, as in the wildest science-fiction.

In effect, the conclusion political economy draws is logical, from its viewpoint. The economists say: as we can't guess at any predictions and since the market is the best mechanism for spontaneous balance, we allow the market to take the control of the exhaustible resources by the price mechanism. If, for instance, world resources of bauxite were depleted, its price would go up and investments in its mines and in products of aluminium would go down. So, the law of market would automatically shift the investments towards other raw materials: frying-pans would be manufactured more and more from steel, airplanes from titanium alloys, and the mobile home beloved of the americans, from plastics. If a resource can't be regulated by the law of market (as in the case of the air we breath, which, since it has no cost, is freely polluted from industries and private people), then the state could intervene to fix its "political price": as to air, for instance, by a pollution tax, whose incomes could be used for public investment or else for fostering private investments in the sector of de-pollution. The various economists stress more or less strongly the regulating function of the state, but statism and free trade doctrine don't affect the general pattern, which is the same for everyone. Their sole aim, as Keynes, their antecedant, openly said, is to avoid unpleasant social consequences, such as general strikes and, God forbid!, revolutions.

Behind complex models and highly mathematical sophistications in most cases there is mere triviality. Were the question simply one of giving prices free reign, well, whom on earth could the state "tax" in order to prevent either the hole in the ozone layer or social troubles? They are phenomena you can't charge to "someone", but to the very existence of mankind with its capitalistic way of producing things and of reproducing itself. It's true that sometimes some young economist whose aim isn't merely to preserve his salary still watches carefully what the computer shows on the screen and realizes how stupid the non-science of economics is, but it's gone in a flash. As soon as the need of bringing home the bacon takes over, he rashly returns to the ranks.

Tomorrow

The revolutionary measures of transition Marx listed in the Manifesto allow us to understand how important the concept of dynamics is: communism is a reality acting continuously, so as to make Capital its own greatest enemy and capitalist society a launching-ramp to the future one.

When Marx lived, a political programme providing for an economy like that of most modern countries today would have been considered as revolutionary. This doesn't mean at all that marxism is supposedly "overcome", for the simple reason that Marx himself analyzes societies and their relevant social relations in connection with the various levels of historical development which they have reached. Besides, already on the occasion of the uprisings of 1848 Marx stresses the dynamics of the revolutions, always tending to overreach themselves: revolution in general is a movement "in permanence". Lenin adds that the economy of the imperialistic age is already an economy of transition.

If we follows one by one the ten points Marx listed in the Manifesto, we see, apart from their literal interpretation, that eight of them have to be rewritten. We see, for instance, that landed property no longer has control of agriculture, which by now is even away from the regular relation of production-market because of the agrarian policies entirely directed by modern states; we see that in all the countries there is the "strongly progressive tax"; that credit is fully controlled by the state-banks, which programme the policy of money and credit; that transportation, communications and energy, whether public or private, are all under the general control of economy, upon which individual capitalists have little effect for quite a long time; that production in the "national factories" has been multiplying, apart from the fact the states are their direct owners or only their suppliers of orders; that integration between industy and agriculture is driven to the foremost; that free state education is an obvious reality; that laws prohibit child labour, and even "the unity of education with material production" is realized, although in such a way as capitalists like (specialized courses, formation contracts, apprenticeship, tutoring, etc.).

Out of the ten points of the Manifesto, only two couldn't be overcome by capitalism itself, as everyone can see, those concerning property, that is, abolition of the inheritance right and confiscation of the properties of those expatriating or rebelling. These are two political measures, typical of a transition phase, when forms of propriety, money and rebellion of the defeated classes still survive, until all of it dies out along with all the classes.

The immediate revolutionary programme which is possible for the countries with a "ripe" capitalism forcefully exceedes Marx's programme. True anticipations of developed communism will be possible simply by freeing potentialities already existing inside capitalism itself, since the full system of capitalistic production would be usable as is, with its very large socialization, its rationalization and its being devoid of the categories of value inside the production process (a product becomes a commodity only when it leaves the productive cycle and enters the market). The capitalists by now are a useless class everywhere, definitively replaced by salaried managers and reduced to being parasitic rentiers . The world economy, in spite of the seeming recrudescence of laissez faire approaches, from the fascist systems on is irreversably fettered in a network of state and inter-statal controls. The social productive force we have reached would right now allow mankind to live a truly human life, if the present anarchy were deleted. Concisely then, it is possible to effect a practical reversal immediately overcoming the social power of production for production to production for mankind.

The prospect of a new society is based on facts, no need for utopian conjectures of a faraway future as a fantasy you can't reach. Science-fiction proves that the products of men's minds are irremediably inferior to a possible reality. Our minds are captives of categories of value because of the existing society that is founded on value, and are unable to describe the future society but by negating the present categories. This is already a great result, and even the transition phase will be more radical than can be imagined. It is not communism yet, but the possibility of applying an immediate programme as described above make this phase a passage during which the revolutionary party will be able to gather together the forces of the whole society and direct them towards the final demolition of the old forms.

The revolution, therefore, is not a fact of construction, but a fact of liberation. There will be nothing to construct, to build, as they used to say during the stalinian counter-revolution, but there will be a lot to demolish, to take away, to free, in order to allow the so far hidden potentialities of the new form to express all of their vital force. Further expanding the social labour and removing the fetters due to this mode of production will be the drives that will "build" the social structure of tomorrow, while the temporary legislator of the temporary state has nothing else to do but study the dynamics of the new form, assimilating its laws of development and abiding by its ends.

The laws of determinism overthrow ancient mystic finalism, but are based on an inexorable formula, which proves to us that the future is inscribed in the course necessary to arrive there, in the same way as the course is established by the possible future. We too have our own finality. Certainly, every complex system – and the human society is highly complex – is very sensitive to initial conditions, but we know that, when a direction is established and the laws of development are well known, the human society itself will be able to organize itself with simple rules, that will be common to all its members. Much more than it is now. This is the condition where a real reversal of praxis will be at long last operating, so that mankind will no longer use its productive power blindly and, as Engels say in Dialectics of the nature, foreseen and projected things will be more and more numerous than the things we encounter randomly.

The modern factory is in no way an anarchical ensemble, it's a living entity, where complex and inter-acting organs integrate themselves, where a collective intellect operates that is denied to individuals. Even more so productive mankind as a whole is a living system, and if the old teleology is dead, the modern theories of evolution, drawn from molecular biology and other disciplines, prove to us that the living being changes according to a dialectic unity of balance and mutation; this is the reason why a sudden change is somehow inscribed in the programme securing genetic stability in a determinate setting. This kind of finalism, a materialistic and dialectic one (teleonomy), is accepted only in a rather rough fashion by contemporary science, which indulges in indeterminism too much, yet more and more scientific events fully confirm the prediction which our current made that the ideological capitulations of the bourgeoisie in the face of marxism were going to increase continually. Recent findings prove to us that in the complex systems, living ones included, structures emerge already containing the items of the future development (the programme) and, above all, that the generalization of this behaviour lets us see the existence of underlying laws at a deeper level. Marx, unlike the utopians, didn't invent anything, he "only" noticed the underlying laws of the most complex mode of production that had so far existed .

When in 1952 the Communist Left said, as quoted in the beginning, that the immediate revolutionary programme should have provided for diminishing the investments in production of means of production as compared with consumer goods, Europe was in the heart of its post-war re-building, therefore still on the way of productive quantitism, which the USA was already leaving and Russia had decidedly taken with Stalin. Today, the Left would re-write that programme in much more precise terms taking into account that in the meantime the American situation has spred to many other countries.

The point is that the immediate revolutionary programme of the next revolution will have easier tasks than in the past, for the simple fact that the social productive forces have overcome productive quantitism. Even the most vulgar of economists admit that the dreadful misery of certain countries doesn't depend on the lack of technical means, but on the lack of capitals. Fifty years ago, there was a gulf between productive investment and production of consumer goods, except for America. Not any longer, now; all over the world industry is actually under-utilized and, with other social presuppositions, it would be easy to stop concentrating production in a few areas and rationally spreading it over the earth. Capital, wage-labour, money, value-accountability can't disappear overnight simply by revolutionary decree, but it will be easy for the bodies of the revolution to use their authority to prevent, for instance, capitals from being directed where they are already strongly concentrated. As you see, you needn't invent revolutionary measures to be enforced by red guards, you have only to address capital's drive to self-destruction. As the Russia and Chinese revolutions proved, decrees are mere pieces of paper if there's not a productive, social and political force behind them to give them a practical meaning.

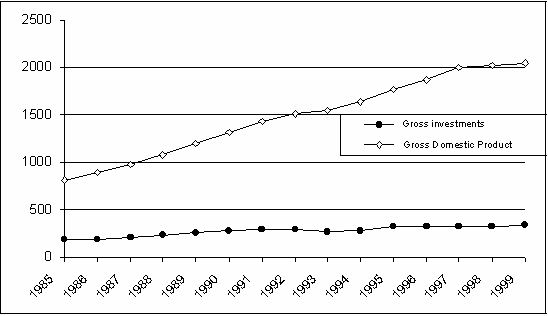

Gap between investment and total produced value. Since in the same bout labour-force in industry diminished too, the diagram shows how much the social production force increased in a country like Italy (Thousands of billions of current liras, data from the ministry of the treasury; • Gross investments; ◊ Gross Domestic Product)

Investment in facilities and raw materials has already decreased, and now it's enough to manage this trend, which is irreversible. Countries like India and China, with their huge populations are scaring the experts of economical trends, who fear that they will reach a Western or Japanese level of production, with an ensuing destructive impact on the environment. But these countries skipped the long path to heavy accumulation as in nineteenth century Europe, so it's stupid to perform such a projection as if they had proceeded in the same fashion. World production is decreasing in terms of quantity, because the production of the developing countries in the field of heavy industry won't make up for its being extinguished in the rest of the world. In fact, modern industry lightens and even dematerializes the items produced in the primary sector of the means of production (better organization, automation, computers, software, communications, etc.).

By the way, the latest crisis in a particular sector is instructive. In 1998 paper pulp had doubled its price, supposedly by a speculation on a foreseen increase in newspaper readers in India and China, which were developing socially and economically like no other country in the past. But this speculation fell short. The Western hunger for paper doesn't depend on an increase of newspaper readers, but rather on an increase of paper utilization in the offices, with their faxes, copiers, printers, etc.). Meanwhile in the West this paper consumption is diminishing because of the digitalization of the data, in the East this step will just be skipped. Information via computer and the internet, which are means China uses collectively, has increased faster than the need of paper files and newspaper circulation. In India, which is becoming the homeland of application software, this phenomenon is even clearer, while in the poorest countries the internet has become the more widespread means of communication, precluding full diffusion of traditional print and mail, by now overtaken.

The ongoing dematerialization of the means of production and goods they produces, is the unconscious product of increasing productivity and competition. But it can become, in the revolutionary immediate programme, a clear and aware strategy of investment constraints, to relieve mankind from the capitalist praxis of production for production. Therefore, it can become a factor for freeing mankind from the need for coerced labour. The potentialities of cybernetics, robotics, data transmission, of the new technologies of the materials are under-investigated in this society searching only for profit. In a society which has passed through this historical obstacle, automation will become freedom from labour as a torment, because of its mercification; eliminating labour time will no longer mean unemployment and super-exploitation, but enjoyment of time for life, conquered at last!

It's not only the product and the means of producing it that will need less matter and energy in their production cycle, but the whole system as well. During the industrial revolution, at the peak of classical mechanization, the machinery for producing and transmitting energy (boilers, pistons, shafts, pulleys, belts and joints) was a mass of material heavier and larger than the tool-machines themselves were; with electric energy and its wired distribution to engines embedded into the machines themselves, all this machinery became obsolete and production was boosted. The pioneer computers weighed a good number of tons, cluttered up large rooms needing air-conditioning, and consumed huge amounts of energy; now, a chip a few millimeters in diameter has a processing ability vastly higher and consumes much less energy than the smallest light bulb.

The process of dematerialization affecting the physical parts of the production system is immensely enhanced by the parallel process of dematerialization of the system itself: it's a matter of fact that putting information into the system makes it "smart". So, the scientific organization in the factories, the so-called parameters of total quality, the rationalization of the relations among the producting parts of the system of related factories, are all immaterial items, that are very cheap as compared with the plants once used, and assist the elimination of stores, administration, stocks, rejects and waste.

Now, all this is nowadays applied very superficially, despite the fact that socialized labour has conquered the whole of the human community. Consequently, we see potentialities struggling to realize themselves, or, as is usually the case, being unable to do so. Let's discuss the case of the printed paper which we spoke of above. In research labs a synthetic paper has already been produced, that can fully eliminate the role of traditional paper. This is a paper-like polymer into which a special printer presses an ink whose particles polarize on the white or black, reacting to the electricity which a printed circuit enbedded in the sheet conducts. In this way any text can be donwloaded by a small connector and memorized in microchips – inserted, for instance, on the cover or spine –, and can be read in a "book" form looking not very different from the traditional one. But is very different in that you, in the same book, would be able to download and read every book written in mankind's history.

It's easy to imagine the potentialities of this system. Once all books in the world are digitalized, everyone will be able to connect to any source and download a fourteenth century incunabulum or Joyce's Ulysses, a single leaflet of the IWW or Diderot and d'Alambert's whole Encyclopédie (its marvelous engravings included), a Liala novel or Einstein's complete works, and, naturally, the complete works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and the "Italian" Left. So, the following will tend to be eliminated : trees for the production of paper, paper mills, printing houses, traditional publishers, book distributors, bookshops, libraries, personal books, shelves to sustain them, picking up paper and recycling it, transport of raw material within this mode, means of production used in the whole mode of production (inks, printing presses, etc.).

This is only a meagre list concerning what can be done with substitutive technologies, since every step is linked to further branches, seemingly detatched, where production quotas would be suppressed as well. Someone could state that new products would replace the old ones, as for our instance, the universal book and the software running it, but they would be mistaken. The implications of the above-mentioned process are deeper than automation or digitalization of CDs replacing thousands of books. We are dealing with quite another question, when we shift from listing quantities of things to qualities of systems.

We may scroll a very long list of instances, from particular goods (cars, home-appliances and numerous kinds of personal devices), to whole systems (the huge information apparatus for value-accountability), and we can also bring into the list energy production and all the questions the plaintive ecologism cherishes, whether moderate or radical. A systematic plan of conscious disinvestment would entail a dramatic curtailment of energy production and usage; which is the only way to realize an energy plan providing for a gradual withdrawal from the so-called non-renewable sources. It's crystal-clear that oil, methane, coal, bituminous seams and uranium will be depleted someday, and that, long before running out, the capitalist rent law is going to produce the skyrocketing of their prices; but picking up the energy of the sun or exploiting other natural sources is simply impossible, when the dominant system is based on the increase of capital. This system is vastly wasteful, not in the trivial sense, meaning that it is lavish, but in the physical sense of the word: its operation requires a quantity of energy larger and larger than the energy it recovers in another form.